To be or not to be (a species)?

Kia ora,

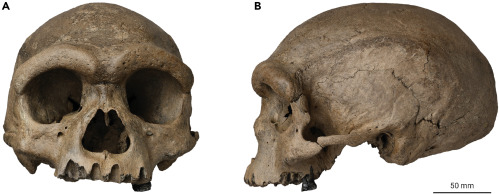

In my last post to this blog I wrote a bit about the Harbin skull, a remarkable fossil find made more than 80 years ago in the city of Harbin in China's Heilongjiang province and that was first announced to the scientific community last year in three papers published in the same issue of the scientific journal 'The Innovation' (Qiang Ji et al. 2021; Qingfeng Shao et al. 2021; Xijun Ni et al. 2021). The cranium is almost complete, but with only one tooth - a huge second molar - and is massive in size, with an endocranial volume of about 1420 ml (larger than the average for modern Homo sapiens - our own species!). Other morphological traits include a prominent supraorbital torus (brow ridge), a very broad (wide) yet orthognathic (flat) face with large, almost square eye sockets, a large nasal opening and delicate zygomatic (cheek) bones, and a cranial vault that is low and elongated when viewed side on. The combination of a wide but Homo sapiens-like face (flat with delicate cheekbones) and an archaic but large-brained cranial vault (lacking the high forehead and globular (spherical) shape that is characteristic of our own species) is described as "striking". I ended my last post by briefly hinting at the intriguing possibility that the Harbin skull is actually the skull of a Denisovan. In this post I'm going to discuss this possibility further.

|

Anterior (A) and lateral (B) views of the Harbin skull. Image from Qiang Ji et al. 2021. |

|

Life reconstruction of the Harbin skull. Could this be the face of a Denisovan? Image sourced from Xijun Ni et al. 2021. |

Recap: What are Denisovans?

The Denisovans are a genetic 'sister' group to Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis) that are currently only known from their DNA and a small number of fragmentary fossils recovered from sites in Siberia (Denisova Cave, after which the group are named) and on the Tibetan Plateau (Baishiya Karst Cave). The Denisovan fossil record recovered to date is so poor that there has been no published description of morphological traits sufficient enough to warrant a scientific species designation like Homo neanderthalensis or Homo sapiens. Confirmation of a fossil as Denisovan currently requires the successful retrieval of DNA or proteins. At the most recent count, confirmed Denisovan fossils recovered from Denisova Cave comprise of

- three worn and incomplete molar teeth

- an incomplete phalanx (finger bone)

- four small, non-identifiable fragments of larger bones, and

- a small, unpublished and apparently not helpfully descriptive fragment of parietal bone from the back of the skull that was announced at a conference in 2019

| |

|

The only currently known Denisovan fossil from a site other than Denisova Cave is an incomplete mandible (lower jaw bone) found in Baishiya Karst Cave on the Tibetan Plateau by a Buddhist monk in 1980 and tentatively identified almost forty years later as Denisovan on the basis of proteomic (protein) evidence. The Baishiya Karst Cave mandible is also known as the Xiahe mandible, after the Chinese county in which the cave is located. The presence of Denisovan DNA in sediment samples recovered during recent excavations has confirmed that Denisovans did indeed once occupy the cave.

To date no DNA or proteins are known to have been retrieved from the Harbin skull. So, what is the basis then for suspecting that the Harbin skull may be the skull of a Denisovan? There are (at least) three lines of evidence to support this proposition. First, there is the age estimate for the skull. As I noted in my last post the best guess as to the age of the Harbin skull is 309,000 - 146,000 years ago. That age estimate window significantly overlaps the date range of presently known Denisovan fossils and sediment DNA, which is from ca. 200,000 - ca. 50,000* years ago at Denisova Cave. In fact, the hominin occupation of Denisova Cave may have begun as early as 300,000 years ago, but whether this was Denisovans has yet to be conclusively established. Regardless of who the earliest occupants of Denisova Cave were, estimates of the timing of the genetic divergence of Neanderthal and Denisovans based on sequenced ancient genomes suggest that this process was well underway by around 400,000 years ago. In the context of these sorts of timeframes the minimum age of 146,000 years ago that has been obtained for the Harbin skull is also not too dissimilar to the minimum age of 160,000 years ago obtained for the Xiahe mandible by dating sediment that was adhered to the fossil.

*Those of you who have read my last post might recall I had a date range of 200,000 - 30,000 years ago. This was based on the dates given in Reich et al. 2010 for Layer 11 at Denisova Cave (50,000 - 30,000 years ago), the layer which the Denisova 3 fossil (the phalanx fragment - replica pictured above) came from. Based on the more recently published work I've re-read since writing that last post (see articles I've linked in this post) I think 50,000 years ago is a more likely date for the most recent Denisovan occupation at Denisova Cave. One big question is about possible post-depositional movement of the Denisova 3 fossil between layers (something which can happen with small objects).

Second, there is the location where the skull was found. OK, so given the circumstances of its discovery we don't know exactly where the skull was found, which I noted in my last post is the reason for the very wide age estimate for the skull. But we do know it was found in China. And in this case that's enough. The identification of diverse Denisovan ancestry in modern Oceanic and East and Southeast Asian populations, as well as additional evidence from sequenced ancient genomes, has led to the inference that Homo sapiens met and admixed with (i.e. got to "know" in the Biblical sense of the word) multiple, divergent populations of Denisovans. This raises the possibility that Denisovans may have once been widespread across continental Asia (obviously including China!) and island Southeast Asia and therefore we would expect that Denisovan fossils will eventually be found at additional locations across this vast region.

The third line of evidence that has some wondering whether the Harbin skull may be the skull of a Denisovan is a fairly comprehensive phylogenetic analysis (modelling evolutionary relationships between the Harbin skull and other fossils based on morphology) carried out by Xijun Ni et al. 2021. Measurements of 634 morphological traits were incorporated into the analysis. The most parsimonious model (i.e. the simplest, requiring the least assumptions) grouped the Harbin skull most closely with the Xiahe mandible, and another fairly complete skull discovered in 1978 in the Chinese county of Dali and tentatively dated to ca. 200,000 years ago.

|

| A section of a larger model of the phylogeny (evolutionary relationships) of 55 fossils from the genus Homo. The coloured boxes indicate a monophyletic group (a group all descended from a single ancestral population). Purple = Neanderthal group, Blue = Homo sapiens group, Yellow = a 'Harbin group' containing the Harbin skull and other Chinese Middle Pleistocene fossils. For the full model see Figure 4 of Xijun Ni et al. 2021. |

|

| Separated at birth?? The Harbin (left) and Dali (right) skulls - two Chinese hominin fossils that bear an uncanny resemblance to each other. Image: John Hawks on Twitter. |

As mentioned above there is proteomic and DNA evidence that suggests that the Xiahe mandible could well be from a Denisovan. Xijun Ni et al. 2021 note that although the Harbin skull was missing a matching mandible the size of its second molar matches the tooth size of the Xiahe mandible and they considered it "reasonable to deduce that the Harbin cranium probably matches a mandible as robust as the Xiahe mandible".

The International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) provides internationally agreed upon scientific standards for the naming of a new animal species. This generally requires the publication in a scientifically recognised publication of a description of the new species based on a 'type' specimen. There's also something called the principle of priority in the ICZN (Article 23 if you're interested in that sort of detail!), which means that the earliest name applied in this way is the correct scientific name.

Qiang Ji et al. 2021 propose that the Harbin skull should be recognised as the holotype of a new species - Homo longi. According to the paper, the species name longi is derived from the geographic name Long Jiang, a common usage for the Heilongjiang province in which the city of Harbin is located and which translates to English as "dragon river". So Homo longi = Dragon Man!

So, IF future work establishes that the Harbin skull is what is currently known as a Denisovan, does that mean that we finally have our first proper scientific species designation for the Denisovans - Homo longi? Not so fast! While 'Dragon Man' is a pretty cool name, it seems unlikely that this species name will stick. According to the ICZN, if two species or two genera are merged for whatever reason, the correct name is the earliest one proposed. The problem for the long term future of the species name Homo longi here is that the name daliensis has previously been proposed for the Dali skull.

Take another look at the photo above that shows the Harbin and Dali skulls side by side. Notwithstanding some of the damage to the Dali skull on the right you would have a hard time convincing me that I wasn't looking at two fossil skulls from the same species, despite the claim by Qiang Ji et al. 2021 that there are "clear [?] diagnostic features" that differentiate the Harbin skull from the Dali skull. And that is without considering the results of the phylogenetic analysis mentioned above that strongly suggest a very close evolutionary relationship between the two fossils. British palaeoanthropologist Chris Stringer from the Natural History Museum in London was a coauthor on the Xijun Ni et al. 2021 paper that introduced the Harbin skull and presents the phylogenetic analysis but not on the companion paper by Qiang Ji et al. 2021 by many of the same authors that proposed the new species name. In some of his own comments on the Harbin skull publicly posted on Twitter Stringer noted that while he agreed that a new species name was warranted, his own preference was "to place the Harbin and Dali fossils together as H[omo]. daliensis." Palaeoanthropologist John Hawks from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, also commenting on Twitter, agreed that IF there is a new species then the name Homo daliensis takes priority under ICZN rules.

But, if Harbin is linked to the Denisovans, is it actually appropriate to name a new species at all? Chances are that, like me, you were taught at school that a species is a group of populations that can actually or potentially interbreed and produce fertile offspring and which are reproductively isolated from populations in other species. This is what is known as the Biological Species Concept, pioneered by the renowned evolutionary biologist Ernst Mayr.

However, past reproductive behaviour cannot be directly observed in the fossil record. Palaeoanthropologists have traditionally had to hypothesize reproductive isolation based on what they could observe in the fossil record - primarily this came down to consistently and persistently distinct morphological differences between groups of fossils. This has been a necessity up until about a decade ago for all hominin fossils and has been the basis for the wide recognition of Neanderthals as a distinct species from Homo sapiens since the nineteenth century.

Then the geneticists came along and started extracting DNA from fossils ...

In light of the genetic evidence that has accumulated over little more than the past decade showing that Homo sapiens, Neanderthals and Denisovans all admixed and must have produced fertile offspring (see some of my previous posts labelled 'Palaeoanthropology' for further discussion of this evidence), many researchers prefer not to think of these groups as distinct species, but alternatively as "subspecies" of Homo sapiens (you might have heard reference to Homo sapiens sapiens or Homo sapiens neanderthalensis), "populations" or "lineages". Xijun et al. 2021 steer away from naming a new species, instead suggesting that the Harbin skull represents a new sister lineage for Homo sapiens.

An evolutionary lineage is a temporal series of populations, organisms, cells, or genes connected by a continuous line of descent from ancestor to descendant. Instead of the classic analogy of an evolutionary tree, some liken our evolutionary history to a braided stream. Like a stream consisting of multiple small, shallow channels that divide and recombine numerous times, human ancestors flowed into different populations, following separate paths for hundreds of thousands of years, yet still coming together numerous times to mix their genes.

|

| Aerial view of a braided river - the Waimakariri River in the South Island of New Zealand. Image: Greg O'Beirne / Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0). |

Thanks for reading,

Nick

Comments

Post a Comment